Results from the Largest ‘Universal Basic Income’ Study in the U.S. Are In. They’re Not Good.

Income dropped. Labor productivity declined. Time unemployed went up. Time spent on childcare and self-improvement didn’t change.

Universal Basic Income, or UBI, has been talked about in academic circles as a potential answer to many of the world’s problems. The policy is just as the name implies: every single adult receives an unconditional check every month, no strings attached. There’s no single cash transfer figure that UBI proponents have settled on as ideal – discussion generally ranges from $50 per month to $1,000 per month.

“Had we had a basic income in place [during the pandemic], that would have been a way of ensuring people are secure, have the ability to meet their basic needs and live a dignified human life,” UNC philosophy professor Doug MacKay said in 2022. “It’s an anti-poverty measure.”

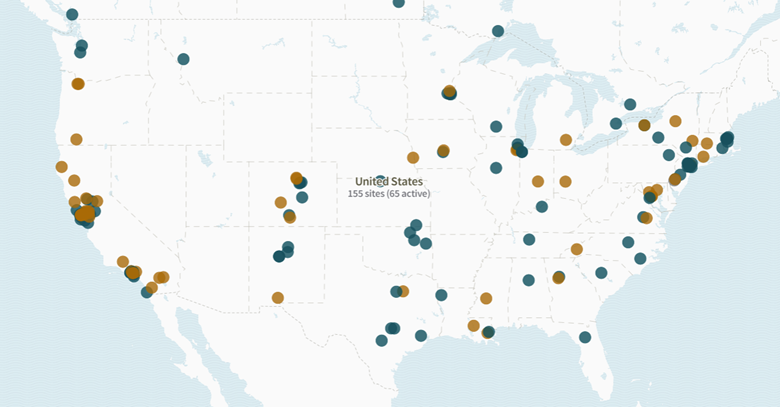

In recent years, UBI has moved out of the faculty lounge and into the real world as a serious policy proposal. Stanford University reports 155 active or concluded UBI experiments in the United States alone:

Source: Stanford University

UBI proponents broadly assert the policy has three main benefits as a replacement or supplement to existing safety net programs:

Self-improvement. UBI lets people with low incomes worry less about immediate financial crises like eviction or medical bills. With those urgent problems set aside, UBI recipients can focus on education or job training, improving their long-term financial and employment prospects.

Efficiency. Existing safety net programs have complicated rules and webs of bureaucracy. The rules are expensive to administer, and they also create perverse incentives (e.g., I’m only going to work part-time because if my income goes up another $3,000, I might lose my housing subsidy). UBI fixes all that because it is unconditional – if you’re alive, you get a check.

Poverty reduction. Proponents theorize that sending people a check each month will result in higher incomes and lower poverty.

The largest randomized controlled trial of UBI in the United States finished up last year. Researchers published their findings just last month.

The study involved 3,000 participants: 1,000 low-income individuals received $1,000 per month for three years, and 2,000 others in the control group received $50 per month. Researchers from UC-Berkeley, University of Michigan, University of Toronto, and University of Illinois examined impacts across dozens of metrics.

The results do not look promising.

The $1,000-per-month treatment group worked less and earned less than the control group. In fact, for every $1 in UBI benefits, total income (excluding UBI) fell by $0.21. Meanwhile, the treatment group did not improve their education or job training in any meaningfully different way than the control group.

So how did those in the treatment group spend their extra time? “The transfer generated the largest increases in time spent on leisure,” the researchers found.

It gets worse. “We can reject even small changes in several other specific categories of time use that could be important for gauging the policy effects of an unearned cash transfer, such as time spent on childcare, exercising, searching for a job, or time spent on self improvement.”

Here are additional excerpts from the study:

“For every one dollar received, total household income excluding the transfers fell by at least 21 cents, and total individual income fell by at least 12 cents.”

“The transfer caused total individual income to fall by about $1,500/year relative to the control group, excluding the transfers.”

“The program resulted in a 2.0 percentage point decrease in labor market participation for participants and a 1.3-1.4 hour per week reduction in labor hours, with participants’ partners reducing their hours worked by a comparable amount.”

“The transfer generated the largest increases in time spent on leisure, as well as smaller increases in time spent in other activities such as transportation and finances.”

“We also saw significant impacts on duration of unemployment. Over the three years of the transfers, the duration of the average spell of non-employment in the control group was 7.7 months; the treatment had the effect of increasing this by 1.1 months.”

“Despite asking extremely detailed questions about workplace amenities, we find no substantive changes in any dimension of quality of employment and can rule out even small improvements.”

“The transfer program studied is particularly relevant to policymakers as it is targeted at lower income individuals, who are the target of virtually all cash transfer programs in the U.S. Individuals between the ages of 21 and 40 whose total household income did not exceed 300% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) in 2019 were eligible to participate, with the bulk of the sample targeted to fall below 100% or 200% of the FPL. Participants reported an average household income of about $29,900 in 2019, so the transfers represented about a 40% increase in household income.”